FROM GIBRALTAR TO CANARY ISLANDS:

30 DAYS AT SEA (AND LAND)

Part 4

Casablanca to Canary

We set sail on a south-westerly course for the 200 km journey from Casablanca to Canary Islands, motor-sailing as wind was light. One night some dolphins visited us and playfully kept us company for half an hour. They don’t jump – just some dark shapes creating a luminous wake, swimming around the boat, forward and backward in a zigzag pattern. Sometimes they aim straight at the boat like a torpedo, and just as you think they will hit, they go under the boat and then reappear on the other side. Throughout the next day the wind continued to drop until the ocean was flat as glass. We kept motoring, hoping the wind will return as the fuel tank does not carry sufficient fuel to get us through all the way. The air was now getting warmer. The ocean changed to a dark blue color from the steel blue of the north Atlantic. The view of the sun setting on a vast, calm ocean is unforgettable.

Four days later we reached Lanzarote, one of the larger islands of the Canary Island chain that rose from an ocean depth of 2,000 meters from volcanic action eons ago. Mostly barren with black volcanic rocks, this island is dotted with tall arid mountains, sandy beaches, and the occasional palm trees, resembling a combination of Nevada desert landscape and Florida seaside. We docked at the city of Arrecife, the largest city on the island with good docking facilities. Cruise ships frequent the port. We are now back to European tourist resort facilities - excellent shops, restaurants and amenities, with the prices to match. Temperature is perpetually at 24C in this dry and sunny climate. After several days on a boat with confined space, it feels great just walking around basking in the sun!

The resort town of Lanzarote

We rented a car to tour the island. Taking a circuitous route, we went through the southern part of the island through some quaint villages, and then started driving north towards the tip of the island. The scenery is mostly volcanic, with fascinating hills and rock formations. A sea of black lava rocks surround barren hills that rise as high as 1,000 meters - remnants of past eruptions. The most recent one occurred in 1736 and buried all the twenty villages nearby. Part of this area is now the Timanfaya National Park. Signs of the fire devil, symbolizing the fiery, barely contained searing heat not far underfoot, can be seen on the highway leading to the park. At places the temperature reaches 140C at just 10 centimeters underground, and at 6 meters below ground the temperature stays at a searing 400C. A restaurant in the park serves fish and meat dishes grilled directly off volcanic heat. A modern museum, magnificently designed with graceful geometric lines that blend with the endless lava fields in the surrounding, documents the volcanic process and natural habitats in this hostile environment.

In the late afternoon we drive through a narrow, winding road and reach the top of the Lanzarote hills. At the summit there is a wind farm, with several rows of huge wind turbines facing the Atlantic. You can see white lines of surfs in the distance, over peaks of black, brown and red volcanic hills against the setting sun. There is not a trace of wind, and in the stillness of the mountain top there is this total quietness, not a sound, just the unmoving fields of black rocks and volcanic peaks against the windmills as if frozen in space and time.

Wind farms at the top of Lanzarote

The next day we sail out of Arrecife and head to the southern tip of the island for a change of scenery. The Canary area is well known for its steady wind that provides great sailing year round, and we are not disappointed. Beautiful blue sky, wind north-east at 15 knots, deep blue water dotted with white caps, with a following sea of one to two meters, the boat merrily slicing through the waves at a speed of 5 knot. By late afternoon we reach our destination, a natural harbor of high cliffs providing shelter from the prevailing north wind. Several other yachts are anchored here. Across our anchorage is a string of beautiful sandy beaches, surrounded by steep rocky hills. The turquoise water is so clear that you can see the sea bottom from 7 meter. The resort town of Fuerteventura can be seen in the distance about 20 km away, and to the west is the open Atlantic, an open expense of dark blue water dotted with white caps under the persistent north wind.

The beautiful beaches at Fuerteventura

At night the wind dies down, but surfs continue to pound the shore with a steady rythym. With no wind to hold the boat in one direction, the boat drifts around and the rumbling sound of the anchor dragging on the rocky bottom keeps us awake.

This wonderful beach area, seemingly quiet and secluded,

turns into a tourist haven by late-morning. Tourist ships drop off loads of

sun-starved visitors, and soon the beaches are filled with people sun-bathing,

swimming, and snorkeling. Towards late afternoon, the tourist boats come back

and pick up all the tourists to return to their luxury hotels. By 4:00PM the

area is completely deserted again and nature reclaims the serenity of a remote

beach where the only sound is the unceasing surfs. In one such afternoon, a

thick, yellowish fog begins to blanket the entire horizon – this is the much

talked-about sand storm of the Sahara. Driven by a steady 20 knot north-east

wind, a cloud of fine sand particles is carried across 100 km of open Atlantic

and shrouds the Canary Islands in a dusty haze. The sun is hidden behind a

pale-yellow sky as it sets, and with the wind rolling

off the hills it suddenly feels cold.

Wallaby Creek at anchor, a sand storm looming in the background

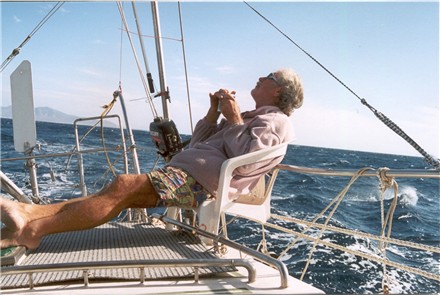

A few days later we lift anchor at sun rise for the final 100 km to Gran Canaria, the largest of the Canary Islands. It is an exhilarating ride, ocean sailing at its best. Wind steady at 20 knots, with the head-sail alone we are running at 6.5 knots. The boat easily plows through the two-meter waves, leaving behind a foaming trail of flattened water amid choppy waves. White caps everywhere. Waves leap up, momentarily illuminated by the rising sun and become translucent – turquoise peaks streaked with white on rippled dark blue valleys of moving water. Sprays cast off from the peaks and are instantly blown back by the wind, spindrifts turning into long, parallel streaks of white foam baring temporary evidence of the direction of the wind and waves. The occasional large waves, coming from abeam and driven by larger gusts, roll the boat to a precarious 40 degree heel, and the boat hangs there momentarily before gravity wins the tug of war and the massive keel returns the boat upright. The water turns into blackish green as it gets deeper – according to the chart, an unfathomable 3,000 meter depth.

Allen enjoying the ocean breeze off Gran Canaria

Twenty four hours later we arrive at Gran Canaria. The harbor at the city of Las Palmas is very crowded, and unable to find berth to dock, we have to anchor off in an adjacent, smaller harbor. With the large swell rolling into the mouth of the harbor, the 10 minute dingy ride to get ashore is a life-threatening exercise. This is a big city. A six lane freeway runs along the coast and separates the port area from the bustling downtown. The north-east tip of Las Palmas narrows into a peninsular, with a long, wide strip of sandy beach facing west, with wonderful views of sun set and the ocean. The beach is crowded with sun bathers, surfers, beach ball players, and the odd swimmers who brave the relatively cold winter water. Along the beach are numerous eateries and hotels. To get a sense of Gran Canaries’ historic roots, one needs to take a hour walk to the south side of town where the Old Town is. Nearly six hundred years ago, Columbus stayed here and used the island as a staging ground before setting sail into the unknown Atlantic and discovering the New World. In the Columbus Museum, a large, old map of the world shows Europe, Africa, and Asia in painstaking detail, with handwritten graphic scripts indicating continents, seas, and cities; and then Americas: A thin slice of the American eastern coastline from north to south, and a totally unknown void to the west.

The famous covered fountain of Gran Canaria, not far from the Columbus Museum

Leaving the coastal cities, narrow

but well-maintained winding roads lead into the mountains. Often the

roads narrow into a single lane that hugs the rocky hills on one side and with a

precipitous fall on the other. Dry, arid land, bare and brown except for the

occasional cactus and small plots of farm, begins to change into greener,

steep rock cliffs covered with pine trees. At the Roque Nublo, a huge rock

precariously perches at one of the tallest peaks of Gran Canaria, A

constant mist surrounds the area as clouds from the Atlantic are trapped in the

mountain range. At a height of nearly 2,000 meters, the air is cold and

brisk with a steady piercing wind.

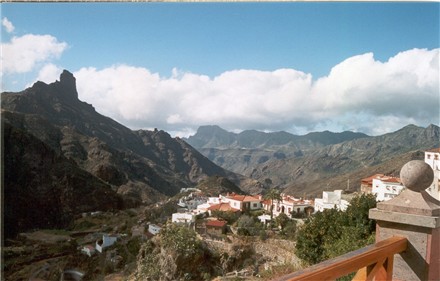

The winding, narrow road leading to Roque Nublo

Driving past this peak, the mountain suddenly opens up into a beautiful valley. An alpine village overlooks the valley, and the horizon is covered by tall, steep mountains extending into the distance. Just then the clouds open up, and as if answering a curtain call a warm November sun brightens up the valley and the white-washed houses below. The village of Tejeda lies in this blessed landscape. Shielded from the cold northern Atlantic wind, warmed by the southern sun, and watered by steady mountain springs, the village flourishes with small farming plots. A local specialty is a type of delicious jam, made of honey, almond and egg, from ingredients that are all locally grown. A small, land-based souvenir, for a very memorable sea-and-land journey.

Tejeda, an alpine village surrounded by spectacular mountain peaks