Seven Days Non-stop Sailing Through the Great Lakes -

An Advanced Sailing Course

Part 2 by Ben Ho March 2009

Lake Erie: True to Its Ship-wrecking Reputation

The southern terminal of the canal ends at Port Colborne and enters at the eastern end of Lake Erie. Lake Erie is the fourth largest of the five Great Lakes, and is the tenth largest lake in the world. It is also the shallowest of the Great Lakes with an average depth of only 62 feet (19 meters). With its numerous shoals and sudden storms, Lake Erie once had a reputation as the grave yard of the Great Lakes in the centuries past. In a gale, Lake Erie’s shallow water creates steep waves which could be more destructive and dangerous than those in an open ocean. In the nineteenth century, hundreds of schooners and steamers were lost here, and numerous wrecks still litter the lake bottom. In the infamous September storm of 1913, a fierce gale blew through Lake Huron and Lake Erie, sending 12 vessels to the bottom with a loss of over 200 lives. Wind gusts of that storm were clocked in excess of 139 km/h (86 mph). With today’s technologies the lake is of course perfectly safe to navigate, and there are substantial commercial traffic and fishing operations. The modern hazards to watch out for are gas wells – Lake Erie has a large deposit of natural gas and there are hundreds of gas wells spread throughout the lake.

As we entered the lake from Welland Canal, a light breeze was on the nose and we motored under a warm, sunny sky towards Detroit at the opposite shore, about 240 nautical miles to the west. After two hours the storm caught up with us from behind, while strangely the wind was blowing from the front. We watched the wind gauge keep going up, until it spiked at 50 knots. The water was choppy, but not overly rough. However with the strong wind on our nose, the engine was overpowered and we inched along at 2 knots. This skirmish with the weather went off and on for two hours with one storm cell after another passing us. We stopped by Port Dover, a pleasant little resort town, to pickup another crew and to stop for supper. We were running late, and it was pass 10:00PM by the time we pulled up at the town dock, which we found to be all deserted and no fuel was available. We celebrated our first port visit with barbecued salmon. An utterly inappropriate choice for stormy seas, as it turned out.

It was close to midnight when we pulled out of the safety of the harbor and continued our westward journey under a moderate breeze. Night watch was kept by a crew of two. Once we crossed Long Point, a 40 km (over 20 miles) sand spit jutting into the lake, the wind freshened and we started to do some serious sailing. Trying to sleep was a real challenge as the boat heeled and bounced around. I realized why lee clothes could be a necessity! Occasionally the boat leaped off a large wave and ploughed into the next trough with a large ‘bang’ that reverberated through the whole boat. Sleeping in the front V-berth became impossible. By the next morning we were all tired, and half the crew had been sea sick and had lost the last night’s meal. I had never experienced sea sickness before – a most uncomfortable sensation! I had one of those pressure patches that applied pressure at the wrist and is supposed to prevent motion sickness – well, it did not work.

Throughout the day we had wind which was moderate but in the wrong direction, and we had to tack frequently. Motoring was not an option, as we were running low on fuel. The extended motoring against strong headwinds the previous day had emptied most of our fuel tank. By nightfall we were approaching the Pelee Passage, a narrow strip of water between a large sand spit known as Point Pelee that juts out 7 nautical miles into the lake, and some small islands and shoals. The waterway was well-marked by numerous buoys, but with a watch crew of two, tacking and man-handling the headsail while trying to keep track of the boat’s position on a paper chart, under a moonless sky sailing in a brisk breeze, it was almost overwhelming. If we had an electronic chart plotter it would have made life a lot easier, but the plotter on the boat was an antique model that did not have the data loaded for this region, rendering it useless except for showing the GPS coordinates. At one point we sailed so close to a large buoy that by the time we realized we needed to tack we were almost on top of it. Of all my sailing exploits, this was the one time that I was seriously concerned about our safety.

Eventually we made our way through the lake and by daybreak

we were preparing to enter the Detroit River, a busy waterway with the ‘Motown’

city of Detroit on one side and the quiet Canadian town of Windsor on the other.

The wind had completely died and we had no choice but to turn on the motor. By

the time we reached the first marina we could pull into, the fuel gauge was

indicating a completely empty fuel tank. It would have been expensive and

embarrassing if we had to request a Sea Tow!

Detroit River, Fuel Gauge - 0

Detroit River, Lake St. Clair, Running Aground

Lake Huron is connected to Lake Erie by two rivers and a smaller lake: Detroit River, Lake St. Clair, and then St. Clair River, covering a total of about 70 nautical miles. The rivers are busy with commercial traffic, as the whole region is densely industrial with large refineries and heavy industries. The river routes are well marked, but some areas are shallow so it is important to keep an eye on the charts. It was interesting to see the Detroit skyline from under the Detroit Bridge, a bit different from the sight one usually sees from the highway. The weather began to clear up when we reached Lake St. Clair. Having motored the whole day, we were looking forward to a bit of sailing through this open body of water, but the wind was not cooperating. We motored through a large regatta of sailboats which were enjoying an afternoon of racing. Somebody had the wisdom to set their race course right in the middle of the waterway, and we had to dart and dodge around them.

By the time we entered St. Clair River, the sun was setting behind us and the sky was a beautiful crimson red. A friendly coastguard boat went by, and then turned around to remind us to turn on our running lights before continuing their way. Two of us were in the cockpit and we both looked around for the light switch. Before we knew it, the boat went off course, and there came this sound that I will remember for a long time – a gentle ‘swoosh’, the sound of a large object being pushed through sand. The boat came to a grinding halt. Luckily the bottom was just sand, there was no wind and the river was calm as a mill pond, and there was still enough light from the setting sun to see. We were not in any danger, just suffering from acute embarrassment. How do you explain grounding a slow-going sailboat in a well-marked waterway, under perfect weather conditions, with little current, or boat traffic? Don’t try. We woke up the rest of the crew, and tried all the textbook techniques of getting a boat unstuck: shifting weight by moving people around, slowly easing the boat forward and backward, changing directions, shifting weight again…reducing weight by getting people off the boat was mentioned, but not attempted (since we did not have a dingy – another important item we should have). The idea is to in effect dig a trench for the boat to get back to deeper water. Eventually it worked and the boat freed herself without damage. What a relief!

Now with the total attention of the entire crew as lookouts, we made it up the river without further incidents. At midnight we pulled into a marina in Sarnia, a large city and terminal port of Lake Huron. Finally able to sleep in our bunks without being tossed about or having to get up for night watches, it felt as good as being in any five-star hotel!

Crossing Lake Huron

Lake Huron is the second largest of the Great Lakes by surface area. It contains the largest fresh water island in the world – Manitoulin Island, which offers shelter to the North Channel from the open lake. The North Channel is rated as one of the best sailing grounds in North America. Unlike Lake Erie, receding glaciers carved a much greater depth in this lake, which has a maximum depth of 750 ft (229 m). The weather became overcast, and then cleared to show a magnificent blue sky reflecting off the deep cobalt water of the huge inland sea. To our starboard, pine forest covered cliffs rose in the distance. To our port, endless water met the sky in the horizon. The wind was light so we motor-sailed with the autopilot set, and we simply rested and read. Compared to the previous days, this part of the trip was completely relaxing and was more like a vacation. Over the course of 24 hours we only came across a few boats. The next day, just after dawn, while getting our first coffee ready, we were startled by a sailboat silently ghosting by, just a few boat-lengths away, with no one on watch. Yes, bad things could still happen in the middle of an empty lake.

The majestic cliffs of the Niagara Escarpment extends all the way from Southern Ontario, through the Bruce Peninsula which like a giant thumb, almost dissects Lake Huron to the east into the Georgian Bay. Bruce Peninsula ends at Tobermory, a naturalist’s haven boasting two National Parks close by - Fathom Five National Marine Park and the Bruce Peninsula National Park. Here one finds the postcard-perfect Georgian Bay scenery: Wind-swept pine trees on rocky outcrops, overlooking crystal-clear water reflecting the deep-blue sky. Far from the city lights of Southern Ontario, this area has a night sky that is left in natural, complete darkness and enables the Milky Way to be seen in its full beauty. But we had no time to linger, and after a quick stop at the Tobermory harbor for a wonderfully filling breakfast, we raised sail and continued towards the eastern shore of Georgian Bay, our final destination. With a gentle breeze on our back, it was easy sailing all the way on this last leg. After we enjoyed a beautiful sunset, darkness set in and we were close to Christian Island, where we were to drop anchor and spend our last night there before heading into port the next day. But the boat had one more surprise for us.

In preparation for anchoring, a member of the crew turned on the windlass to test it. Suddenly, everything went dark. The windlass had not only blown its fuse, but had taken out the entire electrical system. We had no lights, no autopilot, no instruments. We were running the motor at this point, about a mile from land, under a moonless, overcast sky. Land was a dark mass looming ahead. And this is Georgian Bay, where rocks can suddenly show up even in depths of 40 meters. We steered by keeping a compass course, motoring slowly, while part of the crew frantically tried to restore electrical power. Luckily, guided by the sound of gently rolling surfs on the beach and the faint anchor lights of a few sailboats already there, we managed to reach the planned anchorage without incidents. We broke out the champagne to celebrate our last night on the boat.

Lessons Learned

So class, let us recap what we learned from this course:

- Lightning Storm: There is a good chance that those lightning bolts will find other worthwhile places to strike. But it would be prudent to find out about the lightning protection system of the boat, and to have an agreed action plan among the crew.

- A long-distance sail against strong headwind: If you have a choice, don’t do it. However if you find perverse satisfaction in getting to destination by wind power, under any weather, then at least be prepared with plenty of fuel as backup. Strong headwinds have strange effects on engine fuel consumption. Yes, skilled sailors do sail on boats that have no motors, but why tempt fate.

- Running aground: Best solution is, do not do it. And that is achieved by looking ahead.

- Losing electrical power: Actually, it’s not as bad as it sounds. It was not that long ago that people sailed with no GPS, depth sounder, or auto-pilot. (And we’ve already proved that the fuel gauge is not too useful either.)

Happy sailing!

Crossing Lake Huron

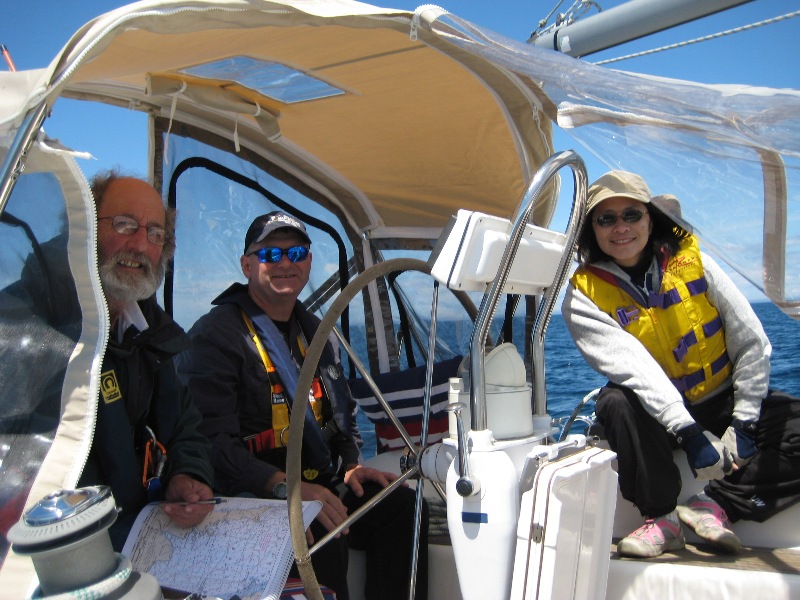

The happy crew